How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Post-Truth

The CM Files, Part Three: "Embrace Post-Truth. Bespoke online learning is better than relying on authority." (Nope.)

I. Introduction

The widespread negative effects of algorithmic Social Media on individuals and societies is well documented. Unfortunately, the field of Media Literacy has not responded strongly to this emerging crisis. I believe when certified smart persons (like teachers, college students, or the intelligentsia) consistently get the wrong answers it’s usually because they’re asking the wrong questions—that is, they’re operating under flawed premises.

I’m reviewing some flawed premises that are IMO disrupting good faith attempts to educate students (esp. regarding Media Literacy). These all sound good—but, upon further reflection, you’re forced to realize that they don’t jive.

In fact, they’re kind of childish. That’s not pejorative, but rather descriptive. “Childish”, in this case, refers to: “simple” OR “infantilizing (to the students)” OR, yes, even a bit “silly”. So…yes. Childish MediaLit.

Welcome back to The CM Files.

II. Truth is Sooooo 20th-Century

The latest flawed premise: We live in a post-truth world.

Well, I’ll just come right out and say it. This framing really isn’t a good idea. For example, when someone asks you “Do you believe in Global Warming?” that’s a stupid question. The proper question is “Do you understand Global Warming?

This is because climate change (like gravity, or coronaviruses, or my waistline after I eat an entire cheesecake…allegedly) is a fact. It isn’t affected by anyone’s beliefs, yours or mine.

Now, because humans are fallible and the scientific method is a process that is always expanding our understanding, our understanding of those facts will change over time. But that doesn’t mean we reject the very processes, like journalism or the scientific method, when they fall short. Planes fly, bridges stand, and polio was eradicated because we learned facts.

But now, as Grandpa used to say: With the high-falootin’ electronical interwebs, everyone has access to everything…and nobody knows nothin’.

Okay, my grandfather never said that. But I actually do often say this: “The average Bank Vice President in 2020 is less intelligent and well-informed than the average Grocery Store Clerk was in 1990.” It sounds glib, but I’m really not kidding. The thing is? I’ve yet to say that to anyone over 50 who hasn’t agreed with me.

How’s that, Internet, for ‘lived experience’?

The good news is that Media Literacy—like best journalism practices or The Scientific Method—is another process we can learn and enact that will really be a force for good. It’s just that, like those other two, there needs to be one thing for it all to do its job. It needs to point to a reproducible (read: authoritative) outcome. From the article:

Science has a neighboring concept worth borrowing: “reproducibility.” A scientist’s findings should be both consistent enough and described well enough that another independent scientist can repeat the research and achieve a very similar outcome.

That’s how it should be with Media Literacy. Far from encouraging everyone to come up with their own truth, or using an AI that will give you three different answers to the same question if asked three different times, we should be encouraging everyone to find—yes their own path, with their own opinions—but ultimately it should be a path to largely shared answer (read: fact). And the process itself should demonstrate shared core values: Y’know, like those words you’re supposed to capitalize: Democracy, Free Speech, Hard Work, Fairness, Listening, (goddamn) Niceness, and a clear Social Justice orientation that never blindly discriminates against anyone, for any reason, because we respect everyone’s Shared Humanity.

Wow, just look at all those old-fashioned ideas (!). And, yes, many are from the mid-20th century ‘liberal consensus’, some as borrowed from the Enlightenment, and are precisely the types of things that so many educators are having a moral panic about now.

I humbly suggest, as educators: We shouldn’t shy away from trying to give the students (and society) the stability of a shared reality.

IIIa. Pitfall #1: Motivated Reasoning

But there are devils in the details.

To begin, this is one area where smart people are at a disadvantage. That’s because smart folks are at a higher risk for having the reverse super-power of MOTIVATED REASONING, as this video points out.

TL:DW is that smart folks are more likely to:

√ Be biased.

√ Fall prey to devoting our smarts to buttressing our own illusions.

√ Not be helped by simple cognitive training (ie, getting better at reasoning).

√ And come up with more and more crazy-pants ideas, using those ideas’ very outlandishness as evidence of their veracity (and as a flex about their own smarts. As in, “Hey! Yo, sorry, but you folks just aren’t hip enough to know how smart this idea really is!”).

In many areas, like Academe, this greater and greater outrageousness leads them to greater and greater acclaim. It’s a recurring (if sometimes hilarious) story. But, the bottom-line is: while maybe less clever people can sometimes be manipulated by others, smart folks manage to manipulate themselves into thinking all kinds of nonsense.

IIIb. What’s Reality Ever Done For Me?

While we’re on the subject of smart people gaining acclaim by spreading crazy-pants ideas…

One noted MediaLit scholar (whom I won’t suffer naming, but all you need to know is that she’s, of course, directly on Big Tech’s payroll) made hay a few years back at SXSW by saying that Media Literacy’s traditional emphasis on teaching “critical thinking” was promoting a skepticism that just made students default to a “nobody knows anything” posture. Okay, yes, there is some research to support that notion. But, then she went farther, suggesting that she was okay with that. She embraced the “post-truth”-iness of it all, and said that we should just be ‘encouraging students to use empathy to understand truths different from their own.’ By the time she was answering the critics of her speech, she had refuted her own earlier statements and, well, like all postmodernists, by the end, her arguments amounted to a nonsensical mishmash. Mostly, she just aimed to be controversial. Mission accomplished.

Of course for people who agree with this line of pro post-truth thinking, the corollary to that is everyone’s viewpoint is valid. In other words, the kids learn: I’m never wrong, because no one ever is! See, learning is fun!

Motivated Reasoning is another form of childishness.

Thankfully, there was plenty of pushback amongst other leading MediaLit scholars. The most obvious counterpoint is that the epistemological crisis (from being online)—by definition—hasn’t been the result of using “critical thinking” online; but, rather, it’s been the result of the profit-driven platforms whose algorithms are promoting more and more extreme positions about…everything. Cause? Meet Effect.

But this hi-tech love of bespoke epistemology, always involving the latest device, and (of course) carrying a hefty price-tag, is nothing new. It’s the logical extension of the Ed Tech wishlist.

What do kids need to learn?

Ed Tech’s answer: “Well, they need to learn how to use these spiffy devices! …Um, …then they need to learn whatever those devices tell them.”

For sure, no longer are the kids supposed to look for the “correct answer”, but rather they should be creating their very own.

And the latest? Teachers and students both are being told (encouraged, even) to use AI tools that simply are not, and can never be, reliable sources of information.

Of course, that doesn’t matter if there’s no objective truth. Oh, and, from a pedagogical standpoint, there no failing as teachers when all we have to do is to get students to ‘consider’ something. Convenient, hunh?

IV. Pitfall #2: Parents Just Don’t Understand

This next form of childishness is even easier.

It starts with this: Kids (especially adolescents) often would rather discover the world away from their families: through friends, and so forth. That is normal, human development. But some educators play into that, currying favor by expanding it into some weird territory, like:

Privacy and Trust are best found online!

OR

The real world is the place where we should be (moral) panicking!

Wrong and wrong.

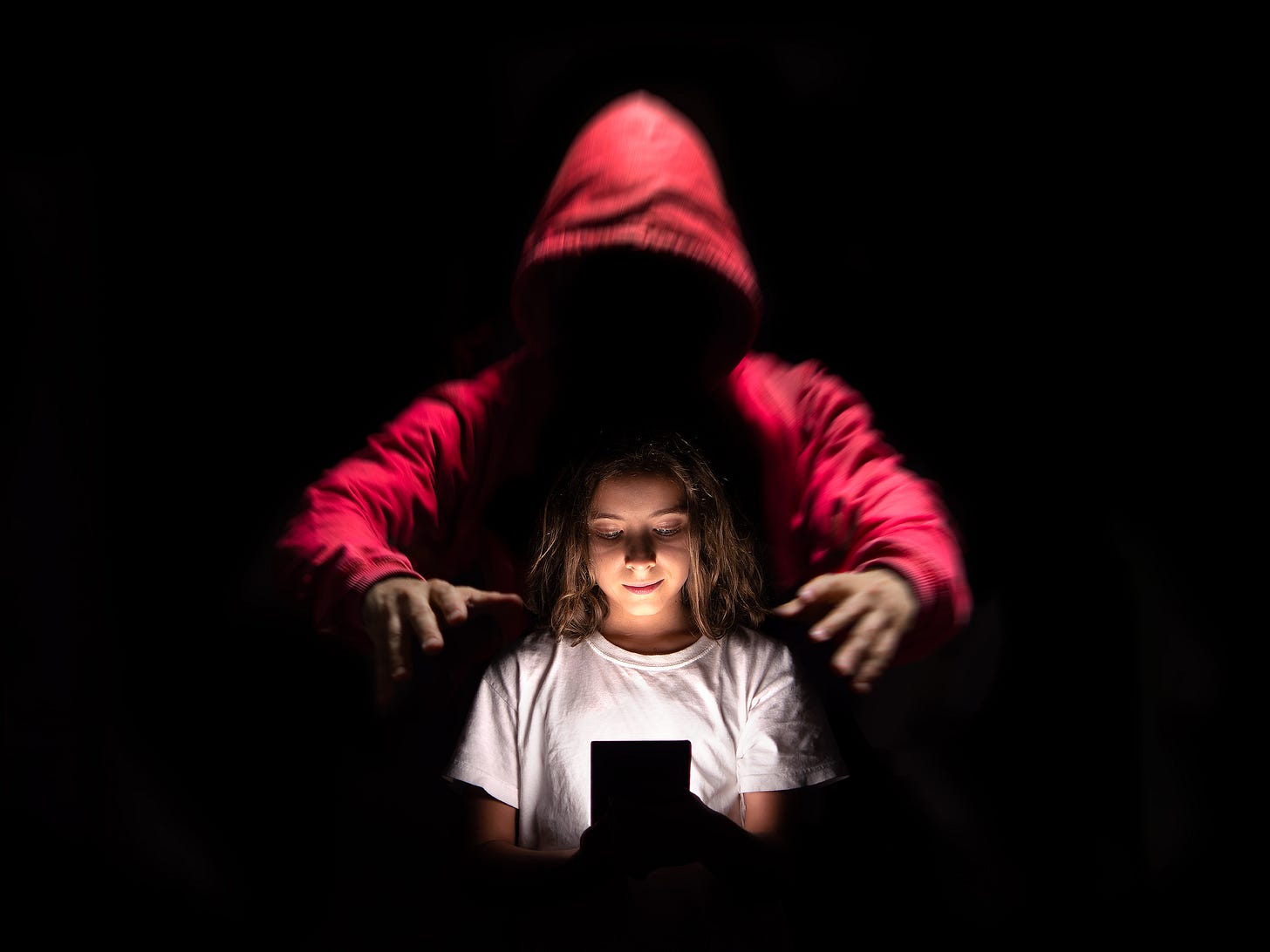

For one thing, kids’ understanding of their own privacy is sketchy at best. A paper that was recently released in the Journal of Media Literacy Education called “What kinds of personal data do primary school pupils share with whom? Children’s view of personal data and its implications for teaching about privacy” contained some interesting data points.

The percentage of 3rd and/or 5th graders that would trust their “Best Friends” with their private information was relatively high (examples: “Who I am a little in love with” = 40%, “Photo of my house” = 80%, and “Photos of me” = 70%). Compared to the percentages that they would share with “All other People” (2%, 4%, and 0%), this is good news. I mean, those numbers for sharing with friends are higher than for sharing with parents…but at least they know not to share with strangers.

—Except, of course, when you consider that many (if not most) of young people’s “friends” are anonymous online randos these days.

Um, yikes?!

PRO TIP: It’s imperative that we let young people know of the dangers of conflating the virtual world with the real one. Truly, the entire concept of an online “Friend” is just one (of the many) “Media Literacy Concepts” that need to be more fully fleshed out for our kids.

SIIDEBAR #2 (ALTHOUGH NOT DISSIMILAR TO THE FIRST ONE). Fellow Gen-X-ers, remember hanging out at the mall when we were kids?

There would always be one mother-daughter duo that walked around dressed exactly the same (it was always dressing like the teen, too…never like the middle-aged woman)? For some educators, this is the goal. Walking in tandem, lock-step, side-by-side with the students. Eternal friends.

Besties.

Yeah, I’m convinced that’s the dynamic behind some of this. Truly a pitfall.

NOTE: it was by no means only a female thing. Back when I taught, plenty of (maybe even more) male teacher colleagues of mine took that approach.

But, I also noticed my students didn’t learn as much from me when I was trying to direct the class in that mode. Things clicked much better when I was the “tough, but fair” teacher. A little mean (to their way of thinking)—but also able to joke around with them.

/// BTW, this vibe is making a comeback just these past few weeks in the political arena...you might know who I’m talking about, Ahem! ///

Anyway, I’m not saying it’s easy; but, lots of the time, kids seek validation when what they really need is guidance.

Even if they do end up gagged with a spoon.

So, is it truly hopeless? What if these kids are too smart to trust their own smarts? Or what if their critical thinking really does lead them into a spiral of mistrust? And—don’t look now—but there are other, similar paradoxes, too! Eeeek!

So, what is the anecdote to this stuff?

Well, clearly, I need to give up and embrace the post-truthiness of it all. Book my own speaking tour…

”Hey, did you hear? Mark said ‘learning leads to stupidness!’

“Ooooh, he’s so edgy!”

V. Potential Solutions

But, no.

As the video points out, it turns out the answer for the kids isn’t to reject authority. It’s to adopt an approach of HUMBLE CURIOSITY.

I don’t have all the answers, but I think I know what the end goal should look like. First of all, let’s be clear: it’s not dependent in any way on AI. Knowledge nihilism is another related concern to post-truthiness.

Rather, maybe it should go something like this? Kids should seek out knowledge from as many authoritative sources as possible. And the youngest children should live (as much as possible) in the real world so that they really do have some lived experience to work with.

And, if we’re looking for metrics of success? We should measure when studuents seek out experts, trust in their own instincts, and especially to be given the ability question others’ ideas and how they got them:

What we call “media literacy” depends on the public taking an interest in the particulars of the journalistic process, not just the stories it produces.

—Journalist Matt Thompson

IF YOU MISSED THEM, parts one and two of this series are at the ← links.

Be well!