I didn't argue that the war in Vietnam was immoral; it was merely stupid and a horrendous waste of time, money, and lives based on a flawed premise.

—Joe Biden (2008)

INTRODUCTION: When certifiably intelligent people (like teachers, or college students) consistently get the wrong answers it’s usually because they’re asking the wrong questions—operating under flawed premises.

This is the second in a series designed to disentangle and debunk some of the those premises. What I’ve noticed? They all share the characteristic of being adolescent wish fulfillment, as in, well…childish. That’s not perjorative, it’s descriptive (defined as: “simple”, “infantilizing (to the students)”, and yes even a little bit “silly”).

Welcome back to the CM Files.

I. Apocalypse New

The above Joe Biden quote is also about a flawed premise. For those of you too young to remember, The Vietnam War (heavy US involvement: 1964-1973, ostensibly in order to “stop the spread of communism”) was considered the United States’ first “lost war” on the world stage.

Now if that’s all it had been it wouldn’t have been such a dagger in the psyche of our country. But, no, it was a horror show. I was too young at the time to realize how bad it was for us, but I do remember some of the news stories. Eighteen year old kids were being forced to go and fight (we still had The Draft) and evidence was being beamed into our living rooms of how poorly things were going—even news stories of war crimes that we were committing were also being reported. By 1973, U.S. troops fled the country that we were (ostensibly) there to protect, in a state of disgrace.

Without getting into whether or not the whole venture was immoral, there are two big things to remember about it.

First, the mood of the nation about ‘Nam shifted in a hurry.

Nowadays, just about everyone takes for granted that the ‘Vietnam War’ was misguided—but in the beginning public opinion had been in favor of it: by a 2.5-to-1 margin in 1964. But, within three short years, public opinion was split. And by 1973 when we left, it was 2-to-1 against. Many of the leading architects of the war itself later wrote books, agreeing that it was all a mistake.

Second, at every stage of the ‘war’, polls showed: the more formal education people had, the more likely they supported the war!

For fans of Media Literacy, this dynamic as exposed by studies of popular support for wars are an excellent example of Chomsky/Herman’s Propaganda Model of Media Literacy.

“Any dictator would admire the uniformity and obedience [to monied/powerful interests] of the U.S. media.”

—Noam Chomsky

But, the premise for the Vietnam invasion was flawed. It was complicated: but, bottom-line, they didn’t want us there. So, from that, there was never going to be a “victory”. But our premise prevented us from seeing that.

Fifty-eight thousand dead American soldiers later, we finally left.

Because we didn’t reject the premise, we ended up doing something a little similar a few decades later in Iraq. And the media/academic support were initially quite uniform about that, as well (TL:DW, Phil Donahue, who was MSNBC’s most popular host, was fired for being anti-Iraq War…he, ultimately, was replaced by Rachel Maddow).

…But ask someone today about whether or not we should’ve done the “Iraq War” and you’ll get a similar answer as with Vietnam.

Today, we have another crisis that’s affecting our young people. You know what I’m going to say. The numbers regarding the negative effects of social media are becoming well known.

√ In the past 13 years, incidence of major depression in 12-17 year olds has more than doubled (that’s 2.9 million newly depressed teens, 3/4ths of which are girls);

√ ER visits by 10-14 year olds for self-harm have tripled (4/5ths are girls);

√ Or with teen suicides (15-19 year olds): A 30% increase over that time frame.

That’s just under 1,000 more children who have killed themselves.

Think of it! One-thousand families who have suffered a needless tragedy. This is all to say nothing of the other negative effects from the addictive technologies that are social media: declining academic performance, sleep disturbance, lack of time spent in the real world with friends and classmates, lack of exercise. And, of course, unregulated access to the internet also exposes young people to other dangers: predators, cyberbullying, and hyper-accelerated peer pressure.

People are noticing the problem (to the tune of about 70% thinking SM is more harmful than not, that’s 10-to-1 compared to those who think it’s the other way around). The Surgeon General has recommended warning labels and restricting young people from social media. Schools are starting to go phone-free. And hundreds of school districts are lining up to sue the Big Tech companies for the addictive technologies that are whoring out our kids’ lives for their profit.

So, what has been the field of Media Literacy’s response to this?

II. “Kids Are Global (Digital) Citizens”

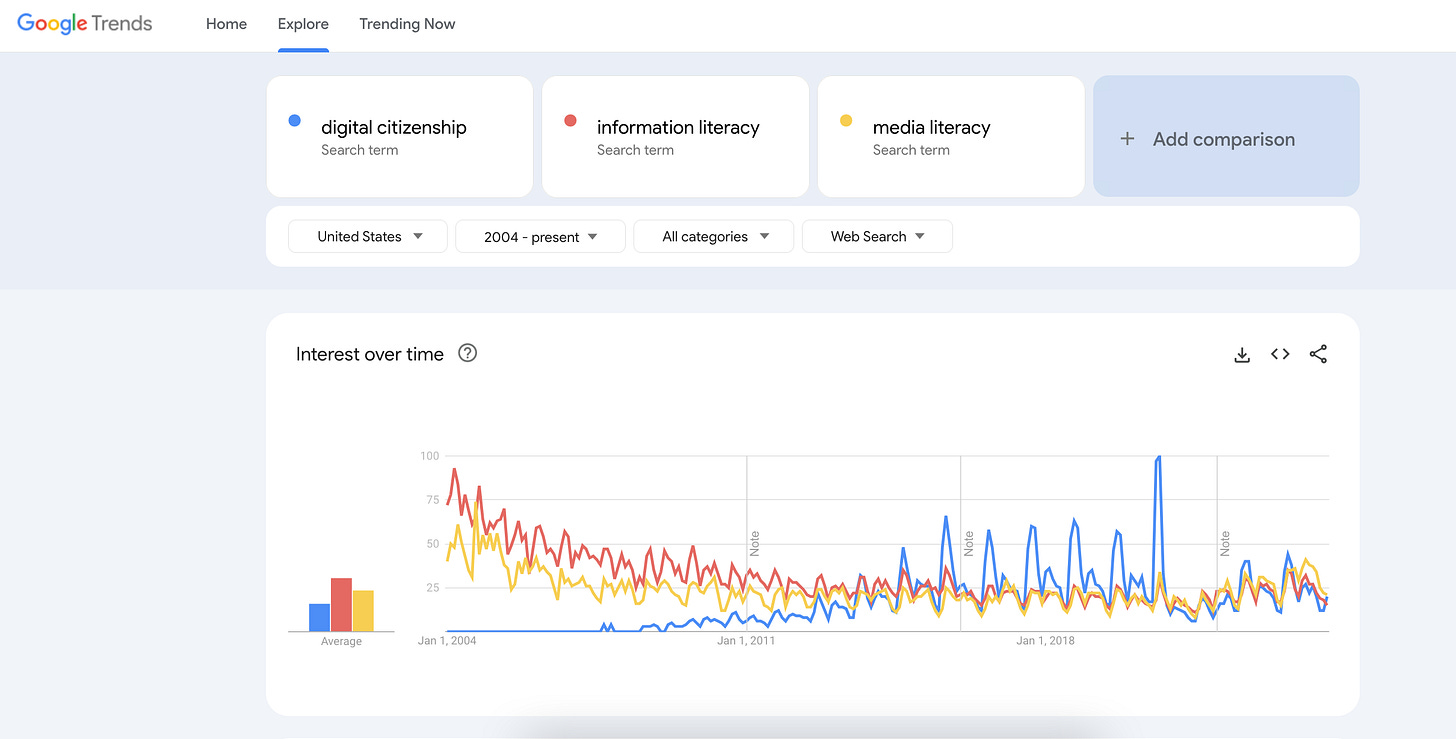

This is a predominate push in the MediaLit space. While #digcit was an obscure branch of the Media Literacy landscape in the aughts, it began to take hold around the same time as the algorithms took over our social media/information landscape. It peaked during the Trump presidency/pandemic, and now is on equal footing with “information literacy” and “media literacy”.

The premise is: Everyone is a “digital citizen”, even kids. The corollary being, since they ought to be “good citizens”, we have to teach them how to do that. And from that, it then follows that we should be getting them online, y’know, to “learn skills” ASAP. Right? That seems self-evident enough. Another bumper sticker-level truism.

But, when we stop and think about it, is it true?

Since “stopping and thinking about it” is a pretty good description of media literacy itself, let’s try it. First, let’s start with: What is a Citizen?

Here’s a definition from Brittanica.com:

Citizenship, relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection. Citizenship implies the status of freedom with accompanying responsibilities.

I’ve read scholars from the school of #digcit who try to conflate this basic definition with the idea of being a part of a “community”. They claim that all that citizenship requires is a community for that person to join—by which they mostly mean having a feeling of belonging to a group.

Of course, that’s a fallacy. If I join a Facebook group (“Dad-Bod Bloggers for Kamala”, or something), I might be a member of that group, but I’m not a citizen of it. Same with anything that happens to me on a game like Roblox—or especially with apps designed to make kids available to anonymous adults like Snapchat. This is because the platforms cannot offer me any rights or protections. After all, they aren’t ‘states’.

Or, to use an example of something that is real: Let’s say I support Ukraine’s efforts to defend themselves against Russian aggression. I might support them online with my posts. I might send them resources. I might even suit up and volunteer to travel over there and help fight. But, none of those things will make me a citizen of Ukraine. And if I suddenly declared myself one of their citizens and then demanded, say, a pension from their government as a right, they would think I was nuts. Так не працює. (“It doesn’t work that way…sport.”)

And yet, that is what Media Literacy educators are telling kids, going as young as Pre-K, every day. You’re online citizens!

How cool is that, hunh?! The kids must love it, I’m sure—since it is obviously childish wish fulfillment.

And it’s also confusing! For example, the kids really are citizens of the United States. So, for starters, wouldn’t they need to understand what that means, first, before we start talking about their online lives? Only in that way would they know what it means to be (or, in this case, NOT TO BE) a citizen anywhere else.

For example, citizens have a responsibility (at least, in a representative democracy) to participate in civic life. To know and follow laws. To vote. Like that. But, make no mistake, long before kids are getting any real civics training (if any) they are being told that they should be on devices.

For example, the Edvolve Digital Citizenship standards for MediaLit say that Pre-K through 1st-graders are supposed to identify “What are my favorite things to do with my device?” (sort of like movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn’s famous leading question: “Tell me, how did you love my picture?”).

Another Edvolve standard is to ask “Why is it important to put devices away even when it doesn’t feel good?” This is a remarkable ask for a 6-year old when they’re facing state-of-the-art software that’s been specifically designed to addict them.

Plus, the kids—excuse me, those little “Digital Citizens”—are also told that they have a responsibility to curate and control their own online experiences (Again, from Edvolve: 2nd and 3rd-graders are supposed to learn to “Choose appropriate sites and apps to find specific information…”). It’s also strongly implied they have some say with regard to regulating those online platforms.

At those ages (4? 6? 8?) especially, this is all pernicious nonsense. It just fills them and adults alike with both a false sense of safety and a false notion of who really is in charge.

PRO TIP, FOR KIDS AND ADULTS: The tech platforms are unaccountable tyrannies. Online, you’re not a citizen at all. You’re a “subject”.

To be clear: I’m not against the ‘digitial citizenship’ framing in all circumstances. In fact, I could see it being done quite effectively at the high school level, or in college. It provides for a nice contrast, a teachable moment.

IV. My Worry

Before President Johnson got us heavily involved in Vietnam in 1964, we actually had already been there for 13 years. At that point we’d lost just under 1,000 lives on the ground there.

Similar to the numbers I list above.

But, then we doubled down. The U.S. figured that, if it wasn’t accomplishing such a worthy goal, then the problem was that it needed to be committing more resources! More troops! More money! And remember, the people who most believed that, were the ones who were most indoctrinated into the prevailing thought leaders. College students were being told what-was-what by college professors at universities who were producing the very PhDs and JDs that were leading the Military Industrial Complex and the Government over the brink.

Similarly, for the past 13 years, Big Tech (and it’s dependent step-cousin, the Ed Tech school movement) has a simple message for us:

More Technology = Good.

And just like with ‘Nam, the educators are on the wrong side of this. Indeed, one of the the four core precepts of the ISTE’s (International Society of Technology in Education) 2007 “National Education Technology Standards for Students” is that everyone must “exhibit a positive attitude about technology”.

Wow. So much for technology just being a tool. It looks like that mantle has been passed on.

But, seriously: who knew it could be that easy? Is this also the solution for fentanyl addiction? Do users really just need to go into it with a more positive frame of mind? At some point, the goofiness grows until education just becomes product placement. And teachers just become pushers.

NOTE: I am not disparaging any specific educators. We should always assume they mean well. Education is a difficult field, truly a public service. It’s simply that, if you’re operating under such a flawed premise—doing technology for technology’s sake (or “learning software skills”)—it becomes another of those worthy goals and something that is presumed worthwhile no matter when we throw at it.

I think there are signs all around us that such blind optimism about the tech is dangerous.

At some point, the goofiness grows until education just becomes product placement. And teachers just become pushers.

The next time a curriculum promises to teach tech skills, just ask “Okay, specifically, what skills?”

I predict you’ll either find the answers to be either i) platitudes (“Be nice.”); ii) info about how to use the product/platform itself (as though that was enough); iii) or you’ll find the skill to be something that is more effectively taught without the tech, like reading or math.

Similarly, speaking as a Gen-Xer who remembers: There also is absolutely zero benefit received from algorithmic social media (like “finding community”, etc) that we all weren’t already receiving before the algorithms—back when the sites were just “Social Networking” sites (Pre-2010). In other words, the Internet used to be better.

V. Keeping it Real

Kids aren’t global citizens—any more than the rest of us are. Stop it.

Cory Doctorow (who I just linked to, above), author and IT activist, nicely sums up the dynamic in another old article:

The problem with being a “digital native” is that it transforms all of your screw-ups into revealed deep truths about how humans are supposed to use the Internet. So if you make mistakes with your Internet privacy, not only do the companies who set the stage for those mistakes (and profited from them) get off Scot-free, but everyone else who raises privacy concerns is dismissed out of hand. After all, if the “digital natives” supposedly don’t care about their privacy, then anyone who does is a laughable, dinosauric idiot, who isn’t Down With the Kids.

No, instead of ‘playing citizen’ in our imaginary online kingdoms, we should keep it real: We are all Global Subjects on the platforms, through which the creepy Broligarchs want to funnel our entire lives—indeed our very identities. In my opinion, Media Literacy Educators, by definition, should know better than to promote this.

Instead, what I often hear from them is blame-the-victim language. Things like ‘negative attitudes about technology will lead to negative realities for the kids’. As though all those million of depressed students were, themselves, somehow to blame.

Or, in other words: “Charlie don’t surf!”

From TikTok challenges to TikTok tics and other social contagions, we already have plenty of examples of algorithms harming the kids. And now, we have a ridiculous tech bubble scam—styled as "artificial intelligence” (AI)—being pushed onto the students as well. I fear that greater and greater roll-outs of AI will be akin to our 1964 doubling down in ‘Nam. Kids turning over their most basic cognitive functions to these new high-tech magic 8-balls, never again knowing (or caring) what a ‘primary source’ might even be—or what the hell they should have been searching for in the first place?

Not good, I say.

I fear a future where generations will be expected to just all ask the same blanket question every morning to their Digital Friend (a device no doubt implanted in their brains) and wait for their respective answers:

“Digital Friend, tell me: Am I a good enough Global Citizen for you?”

How big must the numbers get before we reject the premise?

~~~~~

Feel free to share comments or questions below.

Take care out there, everyone (and Take Greater Care, online).

Here from Carl Hendrick's blog.

Your position/s on EdTech: which specific technology are we referring to, and what is the intended purpose?

Is it Microsoft Word to, say, learn how to create a document? If so, that seems good to me.

Is it Microsoft Word to, say, learn how to create a short video? If so, that seems bad to me.

Is it, say, Duolingo to learn a new language? If so, I would wholeheartedly agree (and even go further)

Or is it, say, something like Anki (or my own Shaeda) or Khan/MathAcademy etc? If so, these seem (and are) great! I'd struggle to see how *these* would impede learning. We already know that the majority of student studying is vastly suboptimal: https://shaeda.substack.com/p/new-study-do-flashcards-work.

Education is arguably (?) the most important thing for society. It's important that we spend time ensuring it's as efficient and effective as it can be. We'd all benefit.

Good read